When designing our dream kitchen from scratch, my husband and I blew the minds of our designer, cabinetmakers and countertop installer by having the temerity to maximize the utilization of our very rectangular space by asking for a deeper workspace on the long edge of our kitchen. (I have documented the issues here.) At 5’10” / 178cm, we are both exactly average male height in America where we are based, as well as my home Australia. We felt that kitchens are typically designed around the housewife, and we would not be bound by that. Look at glue options for kitchen renovations if you need to install new hardware in your kitchen.

“Today, our kitchens still have 36-inch everything, and they still have women in them, mostly; in heterosexual couples in the US, women cook 78% of dinners.”

Here we thought that modern kitchen standardisation was reinforcing sexism by pronouncing the kitchen a space made specifically to fit women’s bodies. Little did we know that the modern kitchen isn’t even well designed around the height of an average height woman in the mid 20th century (5’3″) or today (5’4″).

Indeed, informal questioning of my female friends revealed huge dissatisfaction with modern kitchen design. Kitchens were built to fit women, only they didn’t get the measurements right.

“The problem is the standardizers got it wrong; with designs based on simplified ideals, not reality, women became misfits in their own kitchens and clothes alike.”

So how did the marketing of modernism hijack the kitchen stove?

Table of Contents

Why did the kitchen design stop being utilitarian?

In this excellent article from Treehugger titled “Why Are Kitchen Counters 36 Inches High?“, architect Lloyd Alter asks why the kitchen went from ergonomically designed lower stovetop burners and convenient writing desks, to standardised, flush 36” heights. In short, we can thank the search for a clean look, marketing, fashion, and standardisation. Leslie Land’s From Betty Crocker to Feminist Food Studies finds the “smoking sink”. She writes

“In the early ’30s, countertops were generally about 31 inches tall, while the tops of the—freestanding—sinks were a sensible 36 inches…When the mania for continuous counters decreed that everything from the breadboard to the stove burners to the sinktop must be the same height, the sinktop won, and the 36-inch stove was born.”

And to be fair, yes, having walked into old kitchens where a countertop drops down to desk height, my initial thoughts have been that it breaks up the clean lines of standard heights and makes me feel uncomfortable on a deep level.

We also see this in desks which also used to be a kitchen design element. These days this sitting work space need is commonly met by overhanging countertops with bar stools.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/overall-kitchen-3c22b81dee6c4e29bc40bc1864b87842.jpg)

An ergonomic microwave height

Microwaves come in 4 main options.

- Countertop standalone units. These take up counterspace, but are the cheapest most common.

- Above stove units, integrated with range hoods. This limits your range hood choices, and impacts range hood performance. This higher location is the least ergonomic no matter your height, but particularly terrible for shorter people.

My neighbor installed her oven-microwave with a fold down door at this higher height and has to be careful not to burn her wrists when using it as an oven. - Wall-mounted units, usually above a stove. Expensive, though they look great.

- Drawer microwaves, usually installed under a countertop. Very ergonomical, and suggested for those with accessability needs, including those planning for accessability issues such as arthritis and weakness as they get older. Lifting a heavy plate is much easier from this lower height. Unfortunately these units are also expensive to purchase, starting at $1,000, plus installation, either under a countertop or wall-mounted oven.

We invested in a drawer microwave at the strong suggestion of our kitchen designer primarily to regain countertop space, and couldn’t be happier with that decision. It’s strange for our guests, but repeat guests quickly get used to it. The clean look of a hidden microwave is an added bonus, and should we ever need it, I know we can rely on professional microwave repair services to keep it in perfect working condition.

Can we design kitchens around ergonomics and accessability?

As an accessability-first marketer and person concerned about the resale value of my house, I wanted to make my kitchen comfortable for my husband and I, while not making our kitchen overly-bespoke. We also cook communally, especially if anyone arrives early to a meal. As much as we love our standing computer desk, such a thing would be too unusual in a kitchen. We opted for 36″ high countertops in the kitchen, but 42″ high counters built into our bedroom, nursery and office closets.

We did make one decision knowing shorter people might have an issue – we opted for deeper kitchen sinks. Shorter people are indeed advised to go for shallower sinks or dual-bowl sinks.

Pull down shelves are probably a must for shorter people, or those looking to not stand on a stool to reach something high, however the hardware for each unit is expensive.

Our kitchen offers zero flexibility, other than where you store items, drawer dividers, and adjustable shelf heights. Height adjustable bar stools for the overhanging countertops are an option, and we may opt for that when our children are old enough to do their homework at the kitchen counter. Right now the fixed chairs are the perfect height for us for laptop or pen and paper use. This workspace certainly negates the need for a desk to our great satisfaction.

One deviation from design norms we opted for was to get a deeper (technically, “longer”) countertops on one wall of our very rectangular kitchen. Deeper countertops are not an issue for shorter people. Don’t like a workspace so deep? Don’t use all the space. Little did we know the issues we would encounter, which I have documented here.

Design for neurodiversity

According to Ben Makin, who runs an award-winning holiday home The Lighthouse Keeper’s Cottage, accessability is not just physical. “We respect neurodiversity and have shelves instead of cupboards so it’s easy to find things, our knives and peelers can be used equally well by left- or right-handed people and our appliances are quiet with simple controls.”

Appliance interface buttons: symbols or words, placement, and grouping

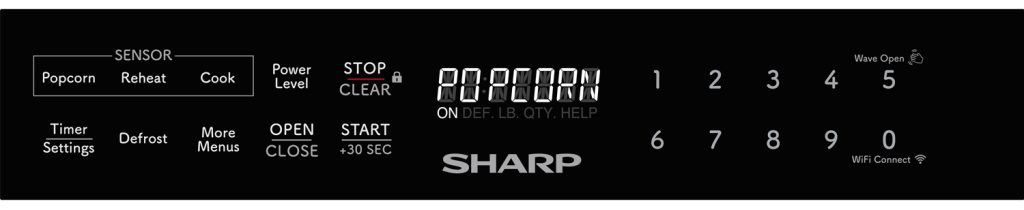

Despite being a native English speaker, with excellent eyesight and a fast reading speed, years into using our appliances I still struggle to find ANY useful button for my GE oven light, and I frequently confuse the the start button for the open/close button on my Sharp drawer microwave.

Here’s my terrible Sharp drawer microwave UI, which seems to be better in some subsequent models:

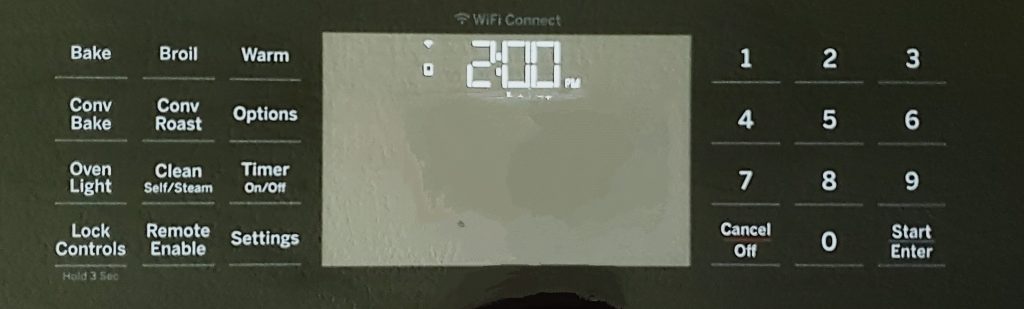

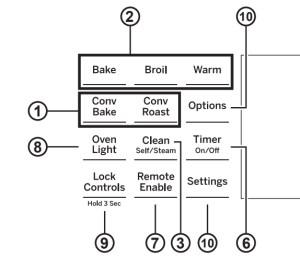

My GE induction range UI’s interface is all text, requiring me to read, read, read, every time I want to turn it on or turn on or off the oven light. Surely they could have used symbols, like 💡 for Oven Light , 🔒 for Lock, ᯤ for Remote, and ⚙️ for settings.

GE could have taken a page out of Sharp’s book, and put boxes around similar buttons. Actually, they did, in their instruction manual, but not in their actual UI!

Unfortunately, intuituve and easy to use UI is something we take for granted on appliances, as other features tend to factor higher in our decision making process. Perhaps we are expected to learn our own appliances UIs, no matter how poor they are.

Capacitive buttons are less accessible

Have you ever pressed a touchscreen or capacitive button and not been sure if the button press registered, or stuggled to find or know where a button is? Capacitive buttons have pros and cons over tradtional buttons.

Capacitive button pros:

- Look amazing

- Easy to clean (essential in a kitchen). You will need to add a “Lock controls” button.

- Save money on manufacture

- Controls can be locked to stop children pressing buttons

Capacitive button cons:

- Zero tactile information to find a button

- Zero haptic feedback to confirm a button has been pressed

- More difficult if pressing the same button multiple times

- Require both visual confirmation and beep. My Philips air fryer’s beeps are ear-piercingly loud, but my Miele dishwasher has a volume control.

- Less pleasurable. People find pressing buttons more pleasurable (see my talk on the topic, which I wrote my master’s thesis on).

Microwaves have always been famously loud, however many do have a hidden mute function.

Car manufacturers are finally listening to feedback and ditching touchscreens in favor of traditional buttons, though no such trend is emerging in the kitchen.

Overall, I find capacitive buttons a good decision for my range, but an unnecessary and frustrating aspect of my portable air fryer, and I love that my panini press has normal buttons. My takeaway is that small, portable appliances should have traditional buttons.

Kitchens aren’t designed for accessibility-first, and that’s a bad thing

Unless you’re designing for a shared space or are a landlord looking to broaden your selling power, it is unlikely you will design with accessibility-first in mind, however, just as in product and web design, it is still a good idea. Even if you are unswayed by the argument of making the world better and more accessible for all, you may benefit from these decisions as you age or get injured, and better accessibility and ergonomics only increase your resale value years down the track. The investment need not be financial, but merely greater thought during the design phase, and I encourage everyone to both do more research, and if you have a kitchen designer, at very least mention accessibility to them as a nice-to-have consideration.

I am of course excluding drastic kitchen custom design that interferes with use by most people, such as designing for someone with dwarfism or designing around a wheelchair is likely to negatively affect house resale price.

Have something you have learnt or contribute? Let me know in the comments.